The Women Who Saved the Fort Pitt Block House

It isn’t always easy to find traces of women’s history in downtown Pittsburgh. But behind one of our iconic buildings, the Fort Pitt Block House, lies the story of how a group of determined, persistent women saved it from oblivion—twice.

The Fort Pitt Block House is downtown’s oldest surviving structure. It’s one of the few traces left of our colonial history. When it was built by British soldiers in late 1763 or early 1764, the American Revolution was years in the future.

Since then, the Block House has survived the American Revolution, floods, the demolition of Fort Pitt, and 130 years of commercial development at the Point. But at the turn of the 20th century the Block House faced its greatest jeopardy.

Round One

The first round of the fight to save the Block House was mostly a fight against neglect and decay. By the late 1880s the Fort Pitt Block House was more than 100 years old. It had been neglected. It was surrounded by a jumble of run-down housing and small businesses.

The Block House was owned at the time by Mary Croghan Schenley. She had inherited most of the land at the Point through her grandfather, James O’Hara. An early Pittsburgh entrepreneur and industrialist, O’Hara had bought the land in 1805.

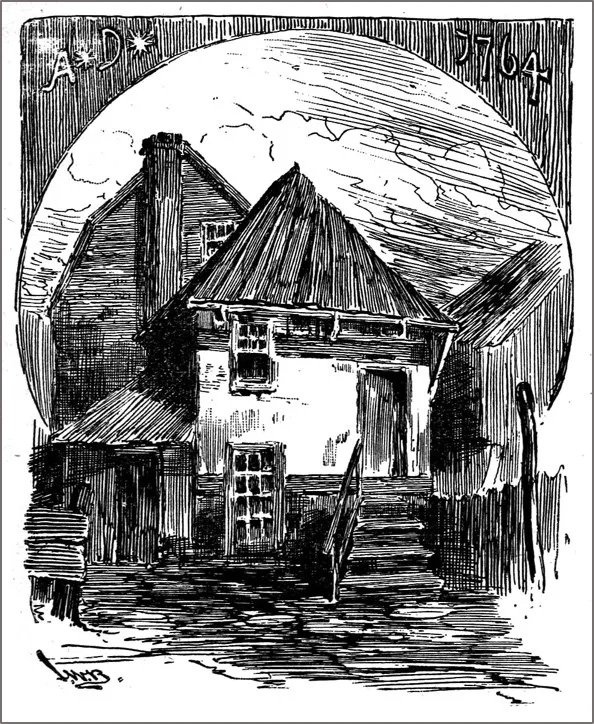

Artist’s Rendering of Fort Pitt Block House, circa 1877 |

Fisher & Stewart’s Guide and Handbook of Pittsburgh & Allegheny via Wikimedia Commons

More than one person with a sense of history had approached Mary Schenley’s local agents about preserving the Fort Pitt Block House. But her local agents wouldn’t cooperate.

Enter the Daughters of the American Revolution. The local chapter was founded in 1891 by women who were—literally—granddaughters and great-granddaughters of Revolutionary soldiers. They included descendants of early Pittsburgh settlers such as James O’Hara, Isaac Craig, and John Neville. Several were Mary Schenley’s cousins on the O’Hara side.

For these women, the Block House was personal. Saving it meant saving part of their family’s history. They eventually persuaded Mary Schenley to deed the Block House to the DAR chapter in 1894. Once they owned it, they moved quickly to restore the building. Then they opened it to visitors.

Round Two

The second round of the fight to save the Fort Pitt Block House started in 1901. On one side were the well-to-do women of the DAR. They envisioned their carefully restored Block House surrounded by a green park.

On the other side: Henry Clay Frick, the Pennsylvania Railroad, and a group of developers known as the “warehouse syndicate.” This wealthy and powerful group saw the Point as a highly profitable development opportunity.

Edith Dennison

Darlington Ammon | Wikipedia

The railroad wanted to extend the tracks that ran down Liberty Avenue at the time all the way to the Point. The developers wanted to surround the railroad tracks with warehouses. There was no place in those plans for the Block House.

The DAR feared the warehouse syndicate would persuade the city to use its powers of eminent domain to remove the Block House. At one point, the developers had offered the DAR $25,000 if they would agree to move the Block House to Schenley Park.

The DAR refused. Led by Edith Darlington Ammon, a great-granddaughter of James O’Hara, the DAR fought for more than 10 years to preserve the Block House where it was.

The Successful Finish

After endless unsuccessful lawsuits against the city, Edith Ammon went to Harrisburg. She persuaded the Pennsylvania legislature to pass a historic preservation bill protecting the Fort Pitt Block House—twice. And she did this in a time when women lacked the vote, and “politics” was considered an unsuitable pursuit for a respectable woman.

The governor vetoed her first bill in 1903 because he thought it gave too much power to the railroads. So Edith Ammon went back to the legislature in 1905. It took two more years, but the DAR got what they wanted.

Fort Pitt Block House, ca 1903 |

John Bragdon, crop of Views of Pittsburgh, Historic Pittsburgh collection via Wikimedia Commons

Edith Ammon wrote most of the bill herself and lobbied for it personally. It became known as “Mrs. Ammon’s bill.” It was one of Pennsylvania’s earliest historic preservation laws. And it saved the Block House. The Fort Pitt Block House is here today because of Edith Darlington Ammon and the other determined women who saw the value of preserving our history.

To learn more about the Fort Pitt Block House, visit http://www.fortpittblockhouse.com/. The Block House is still owned and operated by the Fort Pitt Society chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

This account is based on the book The Fort Pitt Block House by Emily M. Weaver with the Fort Pitt Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, History Press, 2013.

Top Photo: Contemporary photo of Block House: Photojunkie via Wikimedia Commons