Pittsburgh, City of Beautiful Bridges

Of all the bridges in Pittsburgh, which one most represents the city? Is it the Smithfield Street Bridge, Roberto Clemente Bridge, Fort Pitt Bridge, David McCullough (16th Street) Bridge, or another one? The more you think about Pittsburgh’s bridges, the harder it is to determine the city’s best one. This is not often true in other cities. New York, San Francisco, and London are known for having a collection of bridges, yet the Brooklyn Bridge, Golden Gate Bridge, and Tower Bridge stand out among the rest.

Maybe in Pittsburgh instead of an individual bridge, it is a group of bridges that stands out, such as the Fort Pitt and Fort Duquesne pair or the Three Sisters triplet. How can you choose between them? Perhaps because of Pittsburgh’s multitude of unique and significant bridges, the City of Bridges can only be defined by its entire collection.

The reason Pittsburgh has so many noteworthy structures is by deliberate design.

Pittsburgh's Point in 1905, exhibiting privately-built bridges with no cohesive design. | Library of Congress

Pittsburgh's Point in 2020, exhibiting publicly-built bridges with intentional complementary design. | Todd Wilson

In the 1800s, Pittsburgh had a haphazard collection of wooden covered bridges, metal truss bridges, and suspension bridges–all owned by private companies. Architectural design and ornamentation were sporadic at best, as it was up to the individual toll bridge companies, depending on what the companies wanted to provide. Some, like the Smithfield Street Bridge, were elaborately designed and ornamented. Others, like the former Glenwood Bridge that some may remember (it lasted until 1968), were purely utilitarian in nature. The toll bridge era came to an end starting in the 1890s as Pittsburgh was annexing neighboring municipalities. New Pittsburgh residents wanted free movement throughout the city, so Pittsburgh started buying existing toll bridges and building new bridges. This now gave Pittsburgh the ability to control the appearance of new city bridges.

Rejecting trusses, the Art Commission mandated three identical suspension bridges for Sixth, Seventh & Ninth Streets. | Todd Wilson

From 1907 to 1911, Pittsburgh annexed Allegheny City (present-day North Side), becoming America’s eighth largest city at the time. This led to a city government reorganization. Traffic congestion from automobiles was becoming an issue as well, so a planning effort began to modernize city infrastructure with new roads and bridges. The City Beautiful movement, an urban architecture and planning reform philosophy that used neoclassical design principles to bring order and beauty to cities, was prominent at the time. Due to the successful influence of John Beatty of the Carnegie Institute (Museum) among others, the reorganized government formed a Municipal Art Commission in 1911. New civic structures such as buildings and bridges had to secure the commission’s approval to be built.

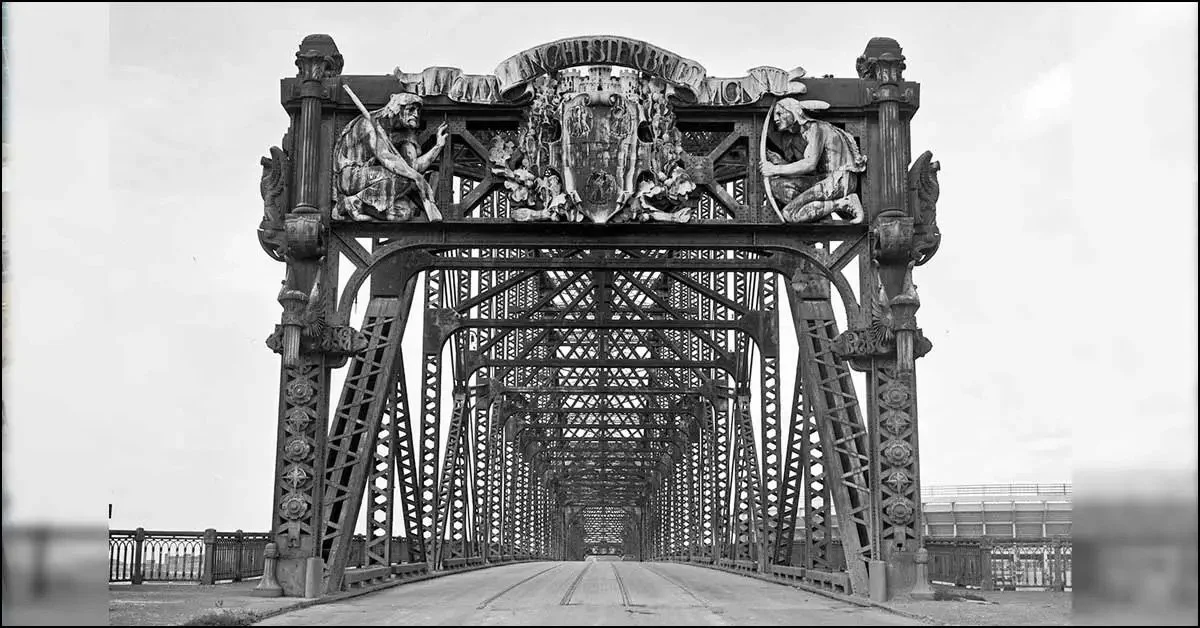

Initially, the private bridges were built without regard to navigation, so the Rivers and Harbors Act was passed by Congress in 1889 granted governmental authority to remove obstructive bridges. The worst offender–the 1875 Union Covered Bridge over the Allegheny at the Point–was demolished in 1907 and replaced by the Manchester Bridge (pictured at the top of the blog) from 1911 to 1915. The new Art Commission’s influence led to a lot of ornamentation being placed on an otherwise utilitarian through truss bridge. Sculptures and other decorations adorned seemingly every Manchester Bridge surface, including giant figures installed over the portals featuring Christopher Gist, Chief Guyasuta (both currently on display by Heinz Field), a millworker, and a miner. While it was the city’s most adorned bridge, the Art Commission did not appreciate its cage-like design that obstructed city views from the road. The commission determined the bridge’s structural design was its primary component of its artistic merit, so the commission started to veto bridge designs they did not think complimented the city. As a result, the Manchester Bridge became the last through truss bridge built within the city limits, though similar bridges continued to be built elsewhere across the three rivers.

In 1917, Secretary of War Newton Baker concluded that all Allegheny River bridges, including the ones the City purchased in 1911 after its Allegheny City annexation, were navigational obstructions and had to be replaced. New bridges had to accommodate a center 400-foot shipping channel and be high enough for river traffic. The first two to be replaced were the last of the private covered bridges, located at 16th Street and 43rd Street. At the Art Commission’s insistence, architecture firms were hired to oversee these projects instead of engineering firms, with Warren & Wetmore in charge of the David McCullough (16th Street) Bridge (1923) and Benno Jansen in charge of the Washington Crossing Bridge (1924). Facing what became a national backlash by groups such as the American Society of Civil Engineers, future bridge projects would once again be led by engineering companies instead of architectural firms.

Next to be replaced were the bridges at Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth streets. The engineers had designed truss bridges, but the Art Commission would only approve suspension bridge designs. There was no suitable way to construct conventional suspension bridge anchorages, so the engineers designed America’s first self-anchored suspension bridges. The bridges were completed between 1926 to 1928.

C. L. Schmitt New Kensington Bridge, built in 1927, shows Allegheny County’s typical truss bridge design. | Todd Wilson

Roberto Clemente Sixth Street Bridge, built in 1928, shows the Art Commission’s design influence. | Todd Wilson

Allegheny County (and later the state) took over major bridge building and implemented their Ultimate Highway System plan (1924-1932), building many of the major roads and bridges we know today. There was a distinct difference between bridges designed within Pittsburgh and beyond Pittsburgh where Art Commission approval was not required. While beautiful bridges were being built in the city like the Three Sisters over the Allegheny (1926-28) and the South Tenth Street (1933) over the Monongahela, more utilitarian bridges were built beyond City borders, such as the C.L. Schmitt New Kensington Bridge over the Allegheny (1927) or the McKeesport Duquesne Bridge over the Monongahela (1928).

Even after World War II, with the construction of the Penn-Lincoln Parkway and Pittsburgh’s Renaissance I project, bridge, design continued to be important. The relatively young Point and Manchester bridges were demolished to create Point State Park and the Fort Pitt and Fort Duquesne arch bridges. Even today, the new Beechwood Boulevard (Greenfield) Bridge over the Parkway East, which could have been a utilitarian structure, was designed as an arch bridge to pay homage to the City Beautiful movement-inspired bridge it replaced.

In Pittsburgh, all but a few major bridges were designed during a period when structural design was at least as important as functionality, if not more. With every bridge designed to make a statement, the city cannot be represented by a single bridge, but only by its collection of noteworthy bridges.

Author’s note on photo at the top of the page: The worst offender–the 1875 Union Covered Bridge over the Allegheny at the Point–was demolished in 1907 and replaced by the Manchester Bridge from 1911 to 1915.