A Radical Remake of Pittsburgh's Skyline

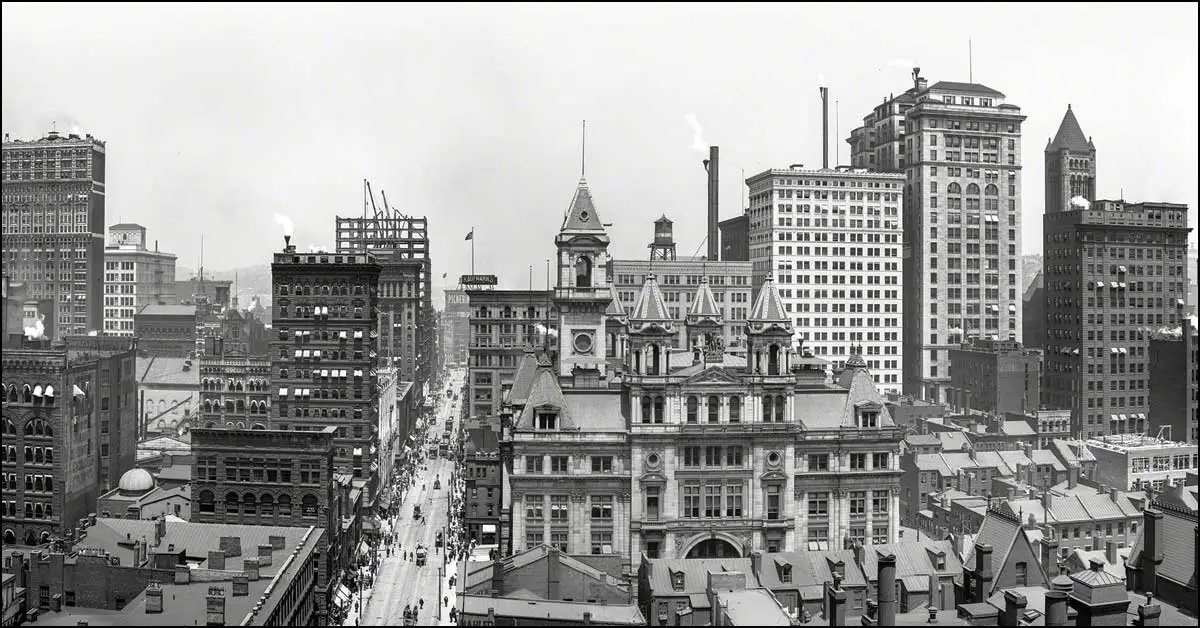

In the decade from 1900 to 1910, the Golden Triangle went from having just two skyscrapers to more than a dozen.

I can’t wait to stay at the Industrialist Hotel, the new boutique inn opening in the Arrott Building at the corner of Fourth and Wood. That gaudily striped 18-story beauty is my favorite Pittsburgh skyscraper. Its picture gets a place of honor on the cover of my new book, MultiStories: 55 Antique Skyscrapers & the Business Tycoons Who Built Them, right on the top row next to New York’s famous Flatiron Building.

Here’s an image of the Arrott from the Heinz History Center’s excellent collection of vintage postcards. I fully agree with the person who mailed this 114 years ago. The building is “going some,” the 1907 slang equivalent of “super cool” or “totally tubular.” And speaking of slang, if “skyscraper” sounds like an exaggeration for something less than one-third the height of the U.S. Steel Tower, you need to shift your perspective. The first elevator-equipped office towers were a shocking technological advancement in an age before cars, airplanes, or radios. And they multiplied rapidly. “There are a number this size here,” as the postcard also notes.

These first skyscrapers—the word comes from old baseball terminology for a high fly to deep center field—radically transformed downtowns across the country in ways we can hardly imagine. We Pittsburghers get excited over one or two new skyscrapers being built in a decade. But the city dwellers of more than a century ago had far more changes than that to cope with.

In 1900, the tallest buildings in the city were the new courthouse and Pittsburgh’s first steel-framed high-rises over 10 stories tall, the technical qualification for a skyscraper. The Carnegie Building is long gone, but the Park Building is still standing near Mellon Square; it’s the one with the crouching atlas figures holding up the roof. Both in 1900 were equally as new to Pittsburghers as the Tower at PNC Plaza is to us today. Yet by 1908, they were dwarfed by far bigger skyscrapers. Henry Clay Frick deliberately erected his eponymous tower to block sunlight from his bitter rival’s building.

St. Paul’s Cathedral on Grant Street

Think about it: The U.S. Steel Tower has dominated our skyline for 50 years. How would you feel if two skyscrapers twice as tall went up next door? I have trouble imagining it. Think of all the refrigerator magnets we would have to throw away.

A row of Fourth Avenue financial district offices are similarly hiding the Arrott in the 1908 photo. But look to the far left, where the new Machesney Building stands alone. Today we call it the Benedum-Trees. That’s because Caroline Machesney, the first woman to build a skyscraper in Pittsburgh, got tired of it quickly and unloaded the property for $10 million to two oilmen, who renamed it after themselves.

Just past the Park Building down Smithfield Street is scaffolding for what was about to become the city’s tallest skyscraper, the 25-story Henry Oliver Building. Its namesake, a Carnegie partner who sourced the Minnesota iron ore that fed the steel mills, was dead by the time of its construction, but his heirs went ahead with the office tower he had ordered from the great Daniel Burnham, planner of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and architect of the Flatiron Building. Yes, that Flatiron. It may be more famous, but the Flatiron is about 50 feet shorter than the Oliver’s 347-foot roofline. The Oliver Building was Burnham’s tallest skyscraper anywhere, and the tallest thing downtown until the Gulf and Koppers buildings came along 20 years later.

The belfries of the city’s first Catholic cathedral, St. Paul’s, are visible next to the Carnegie Building in the 1900 view but overshadowed by Frick’s tower in 1908. The coke tycoon paid the church handsomely to relocate to Oakland. Some say that’s why the structure that replaced the cathedral, Union Arcade—what we now call Union Trust—looks like a church and has two chapels on the roof. A less fanciful explanation is that they are utility structures housing the elevator machinery, and the flamboyant Flemish Gothic terracotta motif was simply fashionable at the time.

What about that castle right in the center of the 1900 and 1908 photos? That’s the main city post office. It’s gone, but some of its sculptures were preserved and now stand outside the Pittsburgh Children’s Museum. It also was “going some,” for sure, but I’d say it was no Arrott Building.

If you’re interested in seeing some of these antique skyscrapers—the Oliver, the Machesney/Benedum-Trees, the Union Trust, the Koppers—from a new perspective, I hope you’ll join me for one of my Antique Skyscrapers Rooftops and Views tours with Doors Open Pittsburgh. The dates are May 22 & 23 and July 17 & 18. Learn more and get tickets.

To learn about beautiful historic high-rises you can see today in cities across America, including plenty within a driving distance of Pittsburgh, pick up a copy of MultiStories and start finding out more about these amazing landmarks hidden in plain sight and the surprising people who commissioned and built them.